There’s a moment that I vividly remember. I’m sitting across from my partner, and we’ve reached what feels like an impasse over a holiday. She wants a camping holiday; tents, campfires, the whole romantic notion of roughing it. I’m advocating for a comfortable B&B; proper beds, warm showers, maybe even room service. We’re both building elaborate cases for our positions, defending arguments about cost, authenticity, comfort, and childhood memories.

We could have continued that discussion indefinitely. Two reasonable people, each convinced of their logic, each subtly trying to win.

Then I asked a question that changed everything: “Is it more important to win on this point, or is the whole point to go on a holiday together?”

What followed was a pause and a shift. Suddenly, we weren’t adversaries defending positions, but we became collaborators exploring possibilities. The solution we found wasn’t a compromise halfway between camping and B&B. It was something entirely different that served what we actually wanted: time together, away from routine, creating memories.

That moment made me reflect on how often we get caught up in the heat of the moment, defending our positions as if our relationship depended on it. But in reality, our relationship thrives on understanding and collaboration, not on winning arguments.

I keep thinking about that moment because I suspect we’re having the same sort of wrong conversation on a much larger scale.

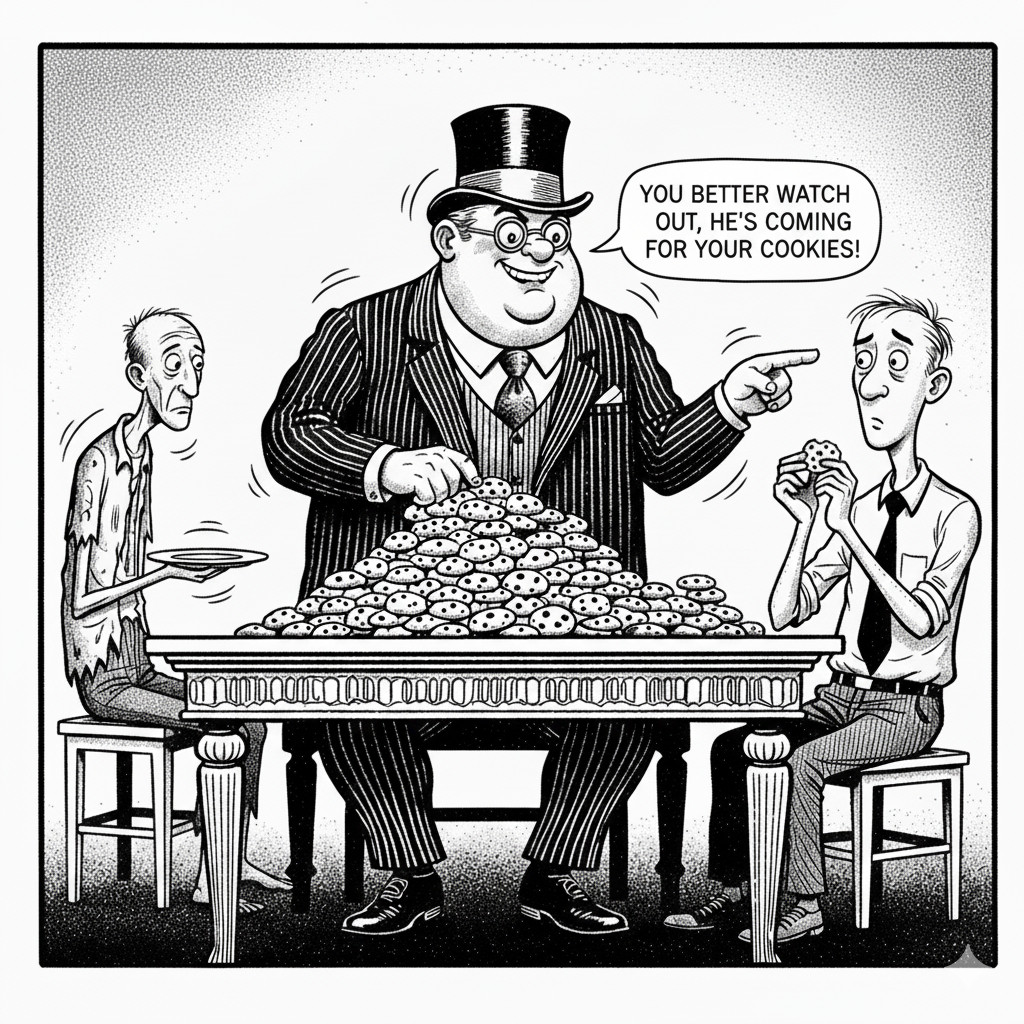

The Cookie Distraction

We let ourselves get captured. Not physically, but psychologically; by forces that benefit from our division. The actions of the Trump, Putin, and Netanyahu administrations dominate our news cycles and, more insidiously, control how we frame our discussions. We react to their provocations, defend against their narratives, and need to organise our thinking around their agendas.

With social media’s ‘snackable’, one-liner discourse, we’ve been sorted into tribes, each with their own facts, their own heroes, their own demons. We’ve become experts at drawing lines in the sand but have lost the art of asking whether we’re even fighting on the right battlefield. It seems like the age-old divide-and-conquer approach is winning over the unite-and-build movement.

Here’s a ‘snackable’ social media example: someone with the most cookies tells the person with fewer cookies that the person with no cookies is coming for them. While they’re arguing, the first person quietly pockets the second person’s cookies, all while the third person, the one with no cookies, is entirely forgotten.

This is what’s happening today; we’re distracted by the noise of conflict while the real issues are swept under the rug.

The Architecture of Division

A Japanese friend once said something fascinating about ‘connection circles.’ In his culture, when an elder enters a room where peers are gathered, the peer circle naturally dissolves and reforms based on respect and legacy. It’s not hierarchy imposed from above; rather, it’s a fluid, cultural understanding of how wisdom and seniority are observed and how relationships adapt to serve collective purpose. This highlights the importance of respect and collective well-being over individual interests.

This stands in stark contrast to what I see around me. Instead of connection circles, we seem trapped in opposition circles, in formations designed not to honor wisdom but to amplify conflict.

This raises the question: are we choosing these formations, or are they being chosen for us?

There’s fascinating research suggesting that trauma and crisis can bring people’s true nature to the surface, with the idea that collective trauma can be countered with collective healing. This draws communities together in remarkable displays of mutual aid and resilience. But there’s equally compelling evidence that division can damage societies beyond repair, leaving fractured identities to remain in conflict.

So which is it? Does conflict unite or divide us?

What Neuroscience Reveals

I suspect the answer lies not in the conflict itself, but in how we choose to engage with it. Are we responding to the actual problems, or are we being choreographed into reactions that serve someone else’s interests?

Consider corporate life for a moment. Sometimes a flat hierarchy works beautifully when everyone shares the same goals and trusts each other to stay on course. Other times, a controlling manager paradoxically creates underground solidarity, where people band together not because of the leadership, but in spite of it.

The structure matters less than the underlying human response to it. The question is how sustainable that solidarity proves to be.

Here’s what behavioral science tells us about our current predicament: social media algorithms aren’t just presenting us with content; they are, in fact, activating our most primitive wiring. Our amygdala, the brain’s threat detection center, is designed to prioritise survival over nuance. When we’re constantly exposed to “us versus them” narratives, our prefrontal cortex (the part responsible for complex reasoning) gets bypassed.

Research on decision-making and social cooperation reveals how this plays out in practice. The more we engage with emotionally charged content, the more we’re conditioned to react rather than reflect. This isn’t accidental. Fear-based engagement drives attention, and attention drives revenue. The more emotionally charged the content, the more our threat detection systems fire, the less capable we become of the kind of thoughtful analysis that complex problems actually require.

But if we’re being played, can we learn to play a different game?

Two Questions leading to Consensus

When I work with organisations caught in internal conflicts, I start with the same two questions I asked myself during that holiday discussion:

“What are we actually trying to accomplish here?“

And then: “Is our current approach serving that goal, or is it serving something else entirely?“

Research on consensus-based decision-making shows it leads to greater commitment and more durable outcomes because the process itself builds trust and collective ownership. People support what they help create. You can see this in action everywhere from Finnish policy agreements to various indigenous governance models such as the Mexican Zapatista movement.

Most of the time, people discover they’re not disagreeing about the destination, but they’re arguing about routes while someone else is quietly changing the map. By focusing on building trust and improving communication, we’re often able to find a solution that everyone can live with.

What would it look like to apply this thinking to our larger conflicts? Instead of trying to defeat opposing viewpoints, what if we focused on understanding the underlying concerns that give rise to them?

The Reframing Practice

Perhaps it’s because I live in the Netherlands, where our political and societal system is formed by what we call the ‘Polder Model.’ Born from centuries of shared struggle against a common threat that is the sea, and the need to unify a wide variety of political pillars (we currently have 15 political parties in our parliament), the Polder Model always seeks a pragmatic and practical compromise. It’s a system built on the very idea that seemingly intractable conflicts dissolve when we question the framing itself.

But could it be applicable as a reframing practice to go against the world’s major issues?

How do we express that we oppose the Netanyahu administration’s policies without being labeled as anti-Israeli? How do we support Palestinian statehood without being accused of supporting terrorism? How do we critique the MAGA movement’s impact without alienating people who feel genuinely unheard by traditional politics?

These aren’t just communication challenges; they’re invitations to think more systemically. What if the goal isn’t to win these arguments but to make the arguments themselves less necessary? What if the real work is building connection circles that make opposition circles obsolete? Imagine a world where we focus on understanding each other’s underlying concerns rather than defending our positions. That’s the power of reframing.

The Quiet Revolution

I don’t think the answer lies in grand gestures or perfect policies. I think it lies in countless small acts of reframing. In choosing collaboration over conquest. In asking better questions rather than defending better answers. In recognising when we’re being choreographed into conflicts that serve everyone except us. Because in the end, there is no Plan B. There is no Planet B. The people we’re arguing with are the people we need to figure this out with.

This is not a loud act. It is a quiet, deliberate one: reclaiming our narrative. One reframing, one conversation, and one collaborative step at a time.

That holiday conversation taught me something: the most powerful question isn’t “How do I win?” It’s “What are we trying to achieve?”

Maybe it’s time we asked that question on a larger scale.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/taking-back-narrative-from-world-conflict-roland-biemans-3raye

Comments are closed