How Music Connects the Past with the Future

Let’s get one thing straight: I am musically illiterate. Hand me a flute, and I’ll clear a one-kilometer radius of all domesticated animals. Give me a violin, and people will scream at the heavens, pleading to be saved from the terror inflicted upon them. I simply cannot play an instrument.

Yet, put me in front of a DAW or a set of turntables, and I can drop beats that will make your head bob and your feet tap. My hands may not know the difference between a C-sharp and a G-flat, but my brain understands rhythm and resonance.

This contrast, this inability to create through traditional means versus the ability to summon profound emotion through technology, is the perfect lens through which to view the common cultural cliché: “Ah, what they call music these days; it’s nothing like we had when we were young.“

This article is about why that statement bears almost no truth about the music itself, but reveals a truth about the human mind and how our memories are formed.

Instant Recognition

It happens in an instant. You mention a band, a tour, a specific concert, and across the table a stranger lights up. “Wait… You were there too?“

And suddenly you’re both talking over each other, reconstructing the setlist, debating whether it rained during the third song, laughing at some shared absurdity that no one else would understand. The bond forms immediately; two people who have never met, now connected through the recognition of a moment in time.

But this recognition is more than just a fun coincidence. It tells us something profound about how memory, emotion, and identity are bound together. And it reveals why music is not simply entertainment, but a core part of who we are; as individuals, as communities, and even as professionals navigating a world where trust and belonging matter more than ever.

Science of Memory and Music

Neuroscience has shown that our memories do not stand alone like neatly stacked files. Instead, they cluster into constellations. Similar experiences fuse into unified sentiments. That is why a single song can bring back not just one afternoon, but a whole season of life.

This is especially powerful in what researchers, such as cognitive psychologist David Rubin, call the ‘Reminiscence Bump’; the period in our teens and early twenties (roughly 10 to 25) when experiences are most vividly etched into memory. During this time, our brains are particularly adept at forming lasting memories, which is why the music we listen to during these years often has a profound impact on us later in life.

Neuroscientist Petr Janata found that music activates the medial prefrontal cortex, a region linked to memory and emotion. It’s how we register and capture the concerts we attended, the songs we played on repeat, the voices we associated with love, loss, or freedom; all of these form part of the scaffolding on which later life memories rest. This is a profound, neurological shortcut to the feeling of being that person at that time.

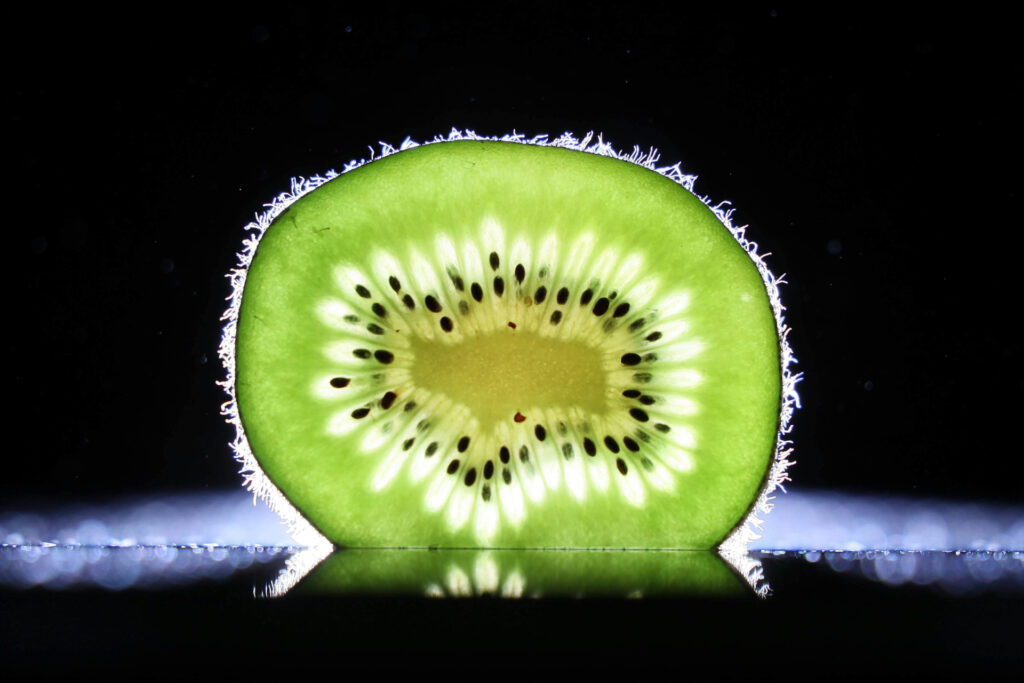

At Yiist, where we help companies explore customer buy-in by understanding how people make sense of complex information and experiences, we often use the Kiwi Model to explain this phenomenon.

Imagine our brain as that tangy sweet fruit. The thin skin represents the language barrier; it’s where we can easily put things into words. The center is where instinct resides. And in-between, the seeds represent emotions and sentiments, fused together into the very structure of personality. Much of what shapes us never crosses the barrier of speech. But it can be carried, expressed, and recognised in art, and, perhaps most powerfully, in music.

Think of the concert again. You may not remember the exact setlist or what you had for drinks. But the pulse of the crowd, the swell of the chorus, the moment when everyone sang in unison; all those elements bypass the language barrier and lodge themselves deeper. You can perhaps verbally express the facts of the experience, but expressing your emotions in words may be a bit harder, because it’s all in your emotional memory.

Years later, recognition happens because someone else’s memory activates the same emotional constellation as your own. While the strangers you met at the concert may be interchangeable, the recognition, however, is immediate. Music makes it possible.

This phenomenon extends beyond personal recollection and creates collective memory. The ‘Pink Panther’ theme, or that of ‘Friends’, the melody of your favourite sports programme, the music from ‘Miami Vice’, the distinctive tune of a popular TikTok song, or even the start-up sound of a Windows operating system. These are all cultural shorthands imprinted in the brain as recognition of a specific moment or era.

Emotional Recognition Across Time

This is why melancholy in music feels so universal. In an earlier reflection, I wrote that melancholy is not the sadness of what is lost, but the beauty of knowing it once was. Music carries that duality. It allows us to feel loss without despair, to remember without getting trapped in nostalgia.

Neuroscience describes this as a shift in brain activity with temporary suspension of analytical regions closely associated with language and explicit thought, allowing other parts of the brain to take over. This is flow or trance — a total surrender to the moment — whether it’s riding a bassline alone at home or dancing in continuous rhythm in an abandoned warehouse with hundreds of like-minded people. In those moments, music becomes pure presence, and later, pure memory.

This recognition across time even explains why musical borrowing resonates so deeply. When a producer samples a drum break, when a jazz musician reinterprets a standard, when a folk singer adapts an ancestral melody; these aren’t acts of theft, but of creative continuity. A motif reused, a rhythm transformed, a sample reimagined: each carries forward something that already lives in our collective memory, creating bridges between generations and genres. I’ve written more extensively about this practice of creative borrowing elsewhere, but the key insight here is that recognition makes the unfamiliar accessible. We respond not to novelty alone, but to the echo of something we already know, transformed into something new.

Why This Matters Professionally

It is tempting to relegate all this to the personal sphere: concerts, playlists, nostalgia. But the implications for marketing, technology, and leadership reach much further.

For Brands: Recognition is more powerful than persuasion. People may forget your slogans, but they remember the feeling of your presence. Tapping into the Reminiscence Bump or a collective memory shortcut is accessing pre-processed emotional capital. A familiar jingle, a recurring theme, even the rhythm of your communication can anchor you in memory.

For Leaders: Trust is not only built through rational arguments, but through the music of speech. Tone, cadence, and resonance. What makes people feel they belong is rarely the words themselves, but the sentiment carried with them and the non-verbal cues that bypass the language barrier.

For Innovators: Music shows us how the new is often a reconfiguration of the known. Creativity thrives not in isolation, but in dialogue with memory; a recognition across time that makes the unfamiliar accessible.

In professional life, just as in music, connection is not built by piling up data points. It is built by creating constellations of meaning that people can recognise themselves within.

Closing Movement: The Paradox of the Listen and the Loop

When people say, “music today isn’t what it used to be,” they are only half right. The music itself may not have declined; rather, it no longer lands inside the reminiscence bump where memories burn brightest. What they are really saying is: “I deeply connect with the person I was when I heard this song for the first time.”

And yet, the thread of music continues to bind. Strangers still meet and leave with a sense of recognition. Songs still carry emotions across generations, and across borders. Music connects the past with the future not by freezing time, but by stitching together experiences across it. It is the art form that tells us: you are not alone, you are not without memory, and you are not without belonging.

So the next time a song transports you, or you meet someone who shares the memory of a concert decades past, pause to notice what is really happening. You are not just recalling a moment. You are touching the structure of who you are. And you are finding that someone else carries a similar seed within them.

That is music as recognition. That is memory as bridge.

Lost in music, found in memory. And recognising ourselves in others.

Interested to learn more about this topic? Read on:

- Janata, P. (2009). The neural architecture of music-evoked autobiographical memories.

- Rubin, D. C. (2005). Autobiographical memory and the reminiscence bump.

- Levitin, D. J. (2006). This Is Your Brain on Music.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/lost-music-found-memory-brain-exploration-yiist-01vse

Comments are closed