The air was alpine, clear, and thin. It was the kind that strips away distractions and lets a different quality of thought settle in. And we had an extraordinary vista of distant mountain ranges piercing through low clouds. We’d been hiking for hours, and by the third time we passed the same local couple on the trail, pleasantries had evolved into actual conversation. By the time we reached the Jausenhütte near the summit and found ourselves sharing a Käseplatte, we were deep into the usual questions: where are you from, what do you do?

I mentioned Eindhoven. Brainport. ASML, the High Tech Campus, Dutch Design Week, Philips.

That’s when I first noticed the slight pause, the unspoken question mark hovering between us.

The conversation drifted toward the influx of international workers, housing shortages, and the changing character of communities. Then came the question, wrapped in genuine confusion and underlying anxiety: “So, all these foreigners are getting all the houses and they get all sorts of benefits, right?”

That was not the point we were trying to make.

We tried to explain what ASML does and what impact it has. We talked about the engineers, the precision work, the global supply chains that depend on what happens in the region. We listed companies, such as Sioux, VDL, DAF, and Philips spin-offs NXP and Signify. We cited organisations such as TNO and BOM, along with a list of notable inventions coming from Eindhoven: the Compact Cassette, the CD, the DVD; light bulbs and LED lighting; X-ray technology and early semiconductor developments. The response was polite bewilderment. A kind of amazed disbelief.

To them, it was an unexplainable phenomenon.

And in that moment, sitting at a wooden table on an Austrian mountaintop, I realised: one of Europe’s most vital technological regions remains fundamentally illegible to most people who don’t live inside its boundaries.

The Problem Isn’t Visibility — It’s Comprehension

Brainport’s success isn’t a mystery in terms of metrics. The economic data is clear. The patent filings are documented. The employment numbers speak for themselves. This isn’t a hidden story; it’s an incomprehensible one.

The strength of this region lies not in flashy consumer products or viral platforms, but in a foundational infrastructure. It’s the machinery that makes the machinery. The processes that enable other processes. The hyper-specialised collaboration networks that most people will never see, even though their lives depend on them daily.

The technical community has become extraordinarily good at internal communication: documenting specifications, coordinating across complex supply chains, and maintaining zero-defect standards. Precision in language matches precision in manufacturing. This hyper-focus on performance optimisation and technical advancement, while necessary for global leadership, creates a closed circuit of understanding. The vocabulary is calibrated to experts. The frame of reference assumes shared context.

The political sphere, the cultural conversation, the everyday citizen trying to make sense of their changing hometown: everything outside that circuit seems to get treated as a peripheral concern. This isn’t malicious; it’s a form of blindness that emerges naturally in high-velocity technical cultures. It’s the implicit assumption that excellence speaks for itself. If the work is globally indispensable, surely its value — and the disruptive side-effects it causes — will be understood.

But the work of translation, of rendering complexity into clear, resonant language, requires dedicated energy. When organisational effort is entirely channeled toward technical output, the function of meaning-making gets deprioritised. It’s seen as secondary, inefficient, perhaps even slightly beneath the serious business of actual innovation.

The cost of this omission is, however, accumulating and damaging.

When Excellence Creates Estrangement

Brainport’s growth generates tangible societal pressures. Housing costs skyrocket, schools struggle to accommodate dozens of languages and educational systems, and public infrastructure is stretched beyond its original capacity. Neighborhoods are transformed faster than social cohesion can adapt.

These aren’t abstract problems. They’re daily friction points that ordinary residents experience directly.

When people encounter these pressures without understanding the systemic source or the ultimate purpose, their natural response isn’t appreciation for economic vitality. It becomes estrangement. It is the sense that priorities have fundamentally shifted away from their community’s well-being, that the benefits are flowing elsewhere, while they absorb the disruption.

This gap between the impact and the understanding represents a comprehension deficit.

The technical achievements are real. The economic contribution is substantial. But the meaning remains inaccessible to those outside the immediate ecosystem. And meaning-making isn’t a luxury; it’s the foundation of social legitimacy.

We must connect this friction directly to the velocity and necessity of the ecosystem.

The need for thousands of highly specialised foreign engineers is non-negotiable for maintaining the global lithography and semiconductor supply chain and, by extension, economic stability. Yet, the community absorbs the immediate social cost of this rapid, globalised requirement. The systemic challenge is not the people, but the speed at which the region must grow to sustain its foundational role.

This stands in considerable contrast to the historical architecture of innovation. The legacy of companies like Philips was built on a pervasive, integrated communal contract with the region. They provided not only jobs but also took care of housing, sports facilities, and cultural institutions. PSV Eindhoven (the football club still carrying Philips in its name) remains a visible reminder of how deeply the company was embedded in the city’s identity. The economic core and the social fabric were interwoven, creating an integrated architecture where the community felt a direct, tangible sense of shared ownership.

Today, the model is fragmented and outsourced. The economic core thrives on hyper-specialisation, while the social consequences are left to be managed by already strained local governments. This distributed responsibility deepens the sense of separation and contributes to the narrative void.

Moreover, within the Netherlands, this disconnect persists on higher levels as well.

National politicians in The Hague and opinion-makers in the Randstad often speak about “the province” as if the south and east still primarily consist of agricultural communities and inherited nostalgia. They overlook the sophisticated value creation happening in Eindhoven, Veldhoven, and Helmond. They also miss the enduring contributions from DSM’s evolution in bioscience and nutrition sectors. They don’t seem to see the strategic significance of cross-border collaboration in the Eindhoven-Leuven-Aachen triangle, or the innovation clusters in Twente and cities such as Enschede and Wageningen. The prevailing perception lags behind reality by at least a decade.

The European Dimension: Where Unity Fractures

If this misalignment exists within a single country, the structural vulnerability becomes existential when scaled to the European level.

The challenge extends far beyond regional misunderstanding. It touches the fundamental understanding of European integration. When the farmer’s daughter in Austria and the TU student in the Netherlands sit across from each other, they inhabit different worlds. Not just in terms of profession or lifestyle, but in their basic assumptions about what matters, what drives progress, what constitutes a good future. Their professional languages don’t overlap. Their daily concerns seem unrelated. Their political instincts will likely diverge significantly.

The European project depends on the premise that cross-border cooperation creates shared prosperity. That pooling knowledge, coordinating investment, and integrating markets benefits everyone involved. But this premise only holds if citizens can actually perceive the benefits. If the connection between “what happens in those technical clusters” and “why my life improves” remains obscure, the entire logic collapses.

What plays out in Eindhoven is not unique. It’s a local expression of a continental pattern, where acceleration in one domain outpaces comprehension in another.

People vote based on what they can see and understand. If they see housing shortages and cultural disruption without grasping the broader context, they’ll support parties that promise to halt the changes. If they experience economic anxiety without recognising how technological infrastructure creates stability, they’ll reject the systems that enable that infrastructure. If the technical community cannot make its purpose felt beyond its own boundaries, it will eventually lose its existential license to operate.

This opacity isn’t merely a communication problem. It’s a foundational risk to the cohesion and shared vision of the European Union.

What Translation Actually Requires

Solving this doesn’t mean generating more press releases or corporate marketing campaigns. It requires fundamentally rethinking how technical communities engage with the world beyond their expertise.

The work of translation must match the precision found in manufacturing. Just as zero-defect standards apply to production, rigorous clarity must apply to meaning-making. This shift needs to move through several interconnected dimensions.

From Specification to Consequence

Instead of leading with what the technology does, it’s better to start with what it enables in human terms. This requires translating the technical objective into a human value. Not the nanometer scale, the processing power, or the defect rates. Not “the world’s most advanced lithography machine”, but “the secure communication infrastructure that protects democratic processes” or “the medical imaging that catches diseases early”.

The technical achievement matters, but only once the human outcome, the consequence, is established as the primary frame. The purpose must precede the performance.

From Facts to Felt Experience: The Hidden Choreography

Lists of companies and inventions glaze eyes over because they accumulate without connecting the dots. The story needs organising principles that people can feel intuitively.

Brainport may best be described through the metaphor of the Hidden Choreography.

This cluster is not a collection of isolated giants; it is a tightly coordinated ensemble. Dozens of specialised, interdependent partners perform a precise, synchronised dance. From the bus manufacturer Ebusco to the mechatronics firms NTS and MTA, the venture-builder HighTech XL, or the precision material suppliers and additive manufacturing experts. The value is in the mutual dependence, the timing, and the collective excellence. Making this abstract principle of coordination visible and tangible, resonates more deeply than any corporate roster because it speaks to the familiar human experience of collaboration and mastery. It renders the complex supply chain perceivable as a deliberate, crafted effort.

From Output to Obligation

The measure of success cannot be volume or velocity alone. It must include the quality of social integration and demonstrated care for the collective environment.

The technical community must hold itself accountable not just for what it produces, but for how it sustains the social fabric that makes production possible. This means integrating local concerns, such as housing supply, cultural resources, and educational capacity, into the central strategic brief.

A social impact statement must be treated with the same rigor and proactive strategy as the environmental impact statement. It is about viewing social coherence as a non-negotiable input, not a disposable output or charitable afterthought. This commitment to obligation is the only way to earn and maintain the social license to operate.

The Fragility of Legitimacy

There’s a dangerous assumption embedded in technical culture: that excellence speaks for itself. That, if the work is good enough, recognition will naturally follow. This assumption is demonstrably wrong.

Social legitimacy isn’t automatically conferred by economic contribution. It’s built through continuous engagement, reciprocal understanding, and demonstrated care for collective well-being. When communities feel unheard, when changes happen without meaningful consultation, when benefits seem concentrated while disruptions are distributed, legitimacy erodes, even if the underlying work is deeply valuable.

A technological ecosystem built without corresponding social and narrative architecture is inherently unstable. It can function brilliantly in the short term, but it accumulates vulnerability. And when resentment builds, political backlash may grow. Eventually, the permission to operate comes into question. The most sophisticated technology in the world cannot survive in a hostile environment.

The Next Form of Precision

The challenge, then, is to develop a form of institutional maturity that matches the technical sophistication already achieved. This means treating comprehension as a core competency, not a peripheral concern. It means investing in translation with the same seriousness as R&D.

If I could distil the insight from that mountaintop conversation to a single point, it would be this: the most urgent precision work happening right now isn’t in cleanrooms or laboratories. It’s happening in the space between what we actually do and what people understand about what we do.

The focus must shift to specific commitments:

- Building educational partnerships that create broader technological literacy across society, not just training engineers.

- Developing narrative capacity within organisations; think of people whose primary job is to make complex work intelligible without distortion.

- Engaging in genuine dialogue with communities, not as stakeholders to be managed but as partners whose input shapes direction.

Most importantly, it requires the humility to recognise that technical excellence, while necessary, isn’t sufficient. That the ability to build extraordinary things must be coupled with the ability to explain why they matter.

I’ve spent years explaining technology to clients, colleagues, and policymakers, and yet that conversation on the mountain reminded me how often we mistake comprehension for communication.

Building that bridge isn’t a distraction from serious work. Making the invisible visible, rendering the complex comprehensible, connecting achievement to meaning is the serious work. Because without it, the social license to continue erodes. Without it, the political support necessary for long-term success disappears.

What’s true for Brainport is true for every frontier field, from biotech to AI to green energy. Wherever specialisation deepens, translation becomes the missing infrastructure.

The unexplainable phenomenon needs to become an explainable reality. Not simplified. Not reduced. But translated with the same care and precision that goes into every other aspect of the work.

That’s the standard worth striving for. And it’s the only way forward that actually holds.

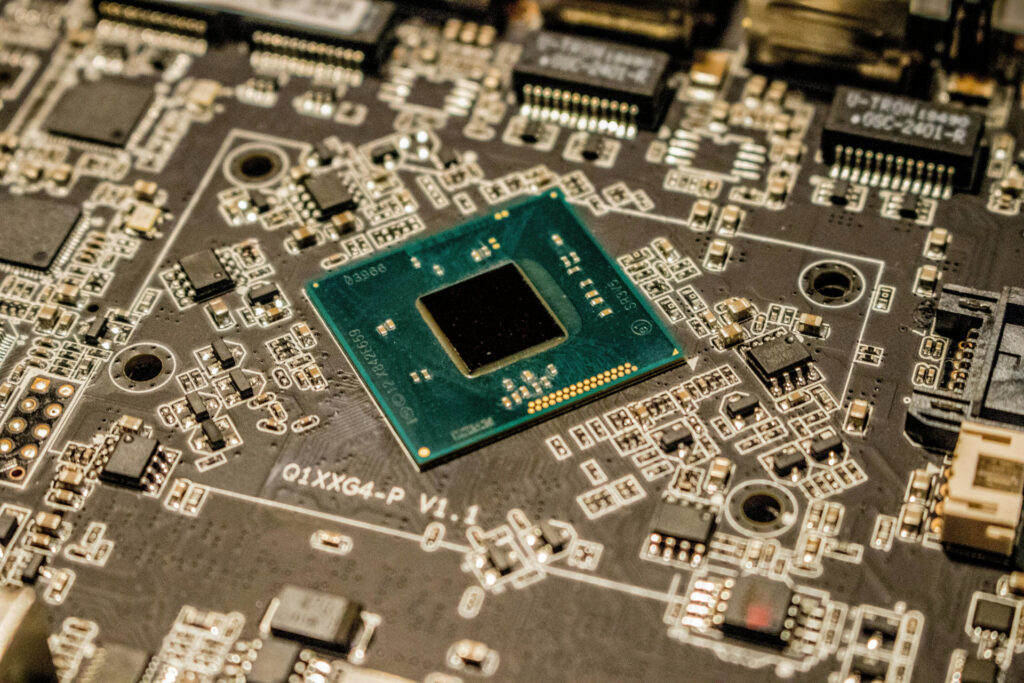

PS – The irony of our conversation wasn’t lost on me later: the photo we took near the summit, instantly sent across borders via our mobile phones, is itself a product of the very lithography, chip design, and material science now so common it requires no explanation at all.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/brainport-why-our-technological-miracles-remain-roland-biemans-sbnxe

Comments are closed